How to use the 1939 Register to find the wartime history of your house

6-7 minute read

By Guest Author | June 8, 2020

The 1939 Register helped me discover who lived in my house before me, writes Professor Deborah Sugg Ryan.

In 1995 I bought a 1934 suburban, semi-detached house in Wolvercote, North Oxford that was like a time capsule. In this article, I describe how I discovered not only the history of my house but who lived in my house, using the 1939 Register and other family records.

From my deeds and searches in birth and death records, I found that the people who lived in my house before me were Vernon Victor Collett (1900-1960), his wife Cecilia (nee Wells, 1897-1995) and their sons Basil Victor Collett (1921-1994) and Roy Vernon Collett (1925-1981).

Deborah's 1930's semi-detached home.

The house was a deceased estate, sold on behalf of the family of the late Cecilia, who died at 98, having lived in the house since it was built. It had only ever been decorated once and still had all its original furniture.

The lounge in Deborah's interwar house.

The 1939 Register helped me find the history of my house. Here are my tips for using it to its full potential when researching yours.

How do I search the history of my house by address?

You can search the 1939 Register by address or postcode via an interactive map.

You can see who lived in any house, town or street in England and Wales shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War on 29 September 1939.

Searching backwards and forwards

As the most recent comprehensive record, the 1939 Register is a great starting point if you’re researching an older house. It is often easier to search backwards from 1939 through census, birth, death and marriage records than forwards from the date that the house was built. It’s also an invaluable resource if you live in a house that was built after the 1911 census. It is especially useful if you’re searching for a house that was destroyed in Second World War bombing. You could even use it if you live in a much newer house that is on the site of a property that existed in 1939.

I had been told by their granddaughter that both Vernon and Cecilia were the first people in their families to own their own homes. The interwar housebuilding boom brought homeownership within the reach of better-off working-class people. Their compact semi-detached 3-bedroom house must have seemed like a dream home.

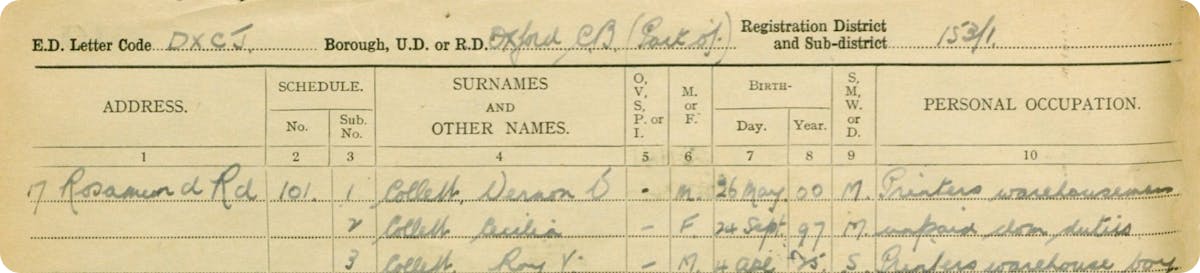

The Collett family on the 1939 Register.

A search of census records revealed that both Vernon and Cecilia were from solid, working-class backgrounds. Vernon was the third of six children of Percy Thomas Collett (1877-1948) and Gertrude Hall (1877-1967). The Colletts were a well-known family of stonemasons (an occupation carried out by Percy’s father) but Percy had broken with the family tradition and worked as a dairyman. Gertrude had worked in domestic service before her marriage and was the daughter of an innkeeper. Cecilia was the fourth of five children of Harry Wells (1860-1910), a house builder (formerly a tallow boiler and labourer), and Sarah Ellen Cox (1859-1951), daughter of a journeyman plasterer. After Sarah was widowed in 1910, she worked as a charwoman to support her family.

What can I find in the 1939 Register?

41 million lives are catalogued in the 1939 Register. You can find details of individuals in the Register: name; gender; address; date of birth; marital status; occupation; whether they were a visitor, officer, servant, patient or inmate; details of inferred family members; other members of the household. It's important to note that it does not include records from households in Scotland, Northern Ireland, the Channel Islands or the Isle of Man. Here's a handy guide for getting started.

Ideal Homes: Uncovering the History and Design of the Interwar House. Order here.

In the case of my house, I was able to find details of the inhabitants’ occupations that I wouldn’t have known otherwise. Vernon’s granddaughter told me he worked at Wolvercote paper mill. The 1939 Register revealed his occupation as a printer’s warehouseman and his son Roy’s as a printer’s warehouse boy, with Cecelia doing unpaid domestic duties.

Top tip: Always look at the original record

Don’t just look at the transcribed record but look at the image of the actual record. Here, you may see extra information on the right-hand side of the image, such as details of voluntary war work. This can give you a great picture of life in your house in the Second World War. For example, I found several of the Colletts’ neighbours worked as ARP (Air Raid Protection) wardens.

When you look at the image of the actual record you might also see names crossed out with another name written in an annotation above or at the side. This records name changes, including women’s subsequent married names. This is because the Register was used to track the civilian population over the following decades and from 1948, as the basis of the National Health Service Register. You can use this information to look for a marriage certificate.

Be aware that names have been redacted to protect the privacy of those still alive. The transcriptions will say ‘the record for this person is officially closed’. In the case of my house, there is a redacted name. However, this may not necessarily be the record for Basil Victor Collett as he died in 1994; it could be somebody else visiting the house. Names are usually made visible when the record of death has been reported to the National Archives. Records are also added regularly for those with birth dates over 100 years ago.

What if I can’t find who lived in my house before me in the 1939 Register?

Care needs to be taken with the 1939 Register as it does not always clearly record who was ordinarily resident at the address and who was a temporary visitor. For example, in my research I’ve found several incidences of one member of a household visiting their elderly parents while the rest of the household stays in the family home. This is entirely understandable at such a time of national crisis when relatives might have required help.

Also, be aware that some households may be missing members who have already been called up for military duties. You can check this by searching for military records. For example, I discovered that Basil Victor Collett joined the Royal Regiment of Artillery in 1938, which perhaps explains that he might not have appeared in the 1939 Register because he was already away on military service.

What if I can’t find my address in the 1939 Register?

View the original document. Don’t rely on the indexes and transcripts. Accurate searching in the 1939 Register is dependent on the accurate transcription of handwritten records. The error might be in the written record itself because the person who wrote it made a mistake. Sometimes handwriting is difficult to read and transcription errors occur. Also be aware that a redacted record of a person may also hide the address if they are written on the same line.

If you draw a blank as you search for an address, you can do the following:

- Try a map search.

- Look for an adjoining street whose name you know in the digital image of the actual record. If you move backwards and forwards through adjoining pages you should find the street you’re looking for.

- If you’re looking for a village, especially where there’s no road address, and it doesn’t appear, try looking for the name of the parish or the nearest larger town.

Correcting errors

This is where you can help. With your knowledge and familiarity of the area and names that you are researching, you can suggest corrections to the transcribed record. You will see a button on the right hand side of the transcription page labelled ‘report an error’ where you can make your correction. It’s helpful to add a comment offering an explanation for your correction.

Where else can I discover the history of my house during World War 2?

Once you’ve found out everything you can from the 1939 Register, here are some other places you could look to find out more about the history of your house in wartime:

- Street and trade directories and electoral registers can help supplement information you’ve found in the 1939 Register.

- Maps can help you understand street numbering, especially if it has changed since the 1939 Register or was different before that.

- Bomb Census survey records (1940-45) are available via the National Archives.

- Your local archives and county record offices might also have bomb records, maps and ARP (Air Raid Precaution) reports.

- A particularly useful resource for London is Bomb Site, which maps the London World War 2 bomb census between 7 October 1940 and 6 June 1941.

- Bomb Site includes photos and stories taken from BBC’s People’s War archive, which is a brilliant resource in itself, covering the whole UK

- Fire service records may detail houses damaged in the Blitz

- Press reports in local newspapers of incidents that happened on your street, such as bomb damage or deaths, can give you an idea of the lives of people who lived in your house in wartime and beyond.

The 1939 Register has so much to offer your house history research. Here are 10 pro tips for making the most of it. We'd love to hear what you've discovered about your home, family or community on the 1939 Register. Reach out to us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter using #WhereWillYourPastTakeYou?

About the author

Deborah Sugg Ryan is Professor of Design History at University of Portsmouth. She is a consultant on all 3 series of BBC Two’s A House Through Time, as well as being an expert onscreen contributor. Her other television appearances include Inside the Factory, David Jason's History of British Inventions, and Number 57: The History of A House. She has also worked for the V&A Museum as a curator and advisor. Deborah's most recent book is Ideal Homes: Uncovering the History and Design of the Interwar House (Manchester University Press, 2020) which was awarded the 2020 Historians of British Art Book Award for Exemplary Scholarship on the Period after 1800. She is currently writing a book about the history of the kitchen and is working with the Science Museum (London) on a project on the history of domestic appliances.

Related articles recommended for you

Five must-read books to discover more about the British Army during the First World War

History Hub

Here's how to overcome nine common house history research challenges: our expert's top tips

Help Hub

Taylor Swift’s family tree shines with love, heartbreak and the triumph of the human spirit

Discoveries