This unique project sheds light on our ancestors' railway accidents

7-8 minute read

By Guest Author | September 16, 2020

Did your ancestor have an accident on the railway? Dr Mike Esbester explains how the Railway Work, Life & Death project can help you discover their stories.

Thankfully, in the UK today our workplaces are relatively safe but it hasn’t always been that way. Only just over 100 years ago working on the railways was both common and incredibly dangerous. The railways employed over 600,000 people in 1913 – nearly 30,000 of whom had an accident. Bad news for them and their families. The good news for family historians is that sometimes the accidents produced helpful records.

Find railway relatives and much more

Enter a few details to see your family's records at your fingertips.

Accidents on the railways

Those records tell us more about the people involved, what they were doing and what happened next. The trick is finding them.

Fog, snow and death

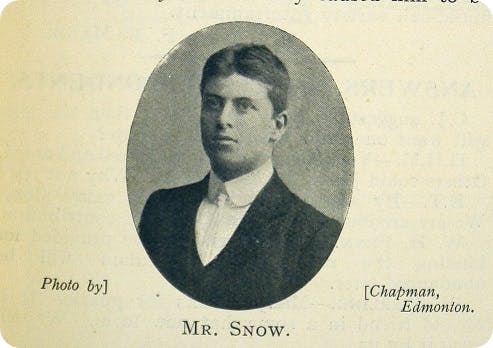

Early in the morning of Friday 3 February 1911, 24-year-old Joseph Snow was killed in the enormous Temple Mills goods yard in east London. He was walking home from his shift as a Great Eastern Railway goods guard (someone who rode at the end of a freight train to oversee pick up and drop off of wagons).

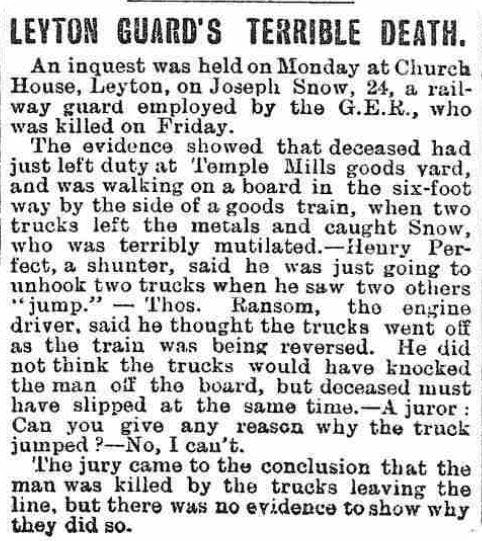

Unfortunately for Joseph, as he walked alongside the tracks something happened – though exactly what is unclear. According to a press report of the inquest, a wagon derailed and caught him.

Chelmsford Chronicle, 10 February 1911.

According to the official accident investigation;

"Snow missed his footing…and fell between the wagons"

This killed him and derailed the wagons. Joseph had been on duty for around 14 hours when the accident happened, two hours longer than he should have been, as a result of fog. Was he tired, causing him to slip?

Why was railway work so dangerous?

Well, for some railway workers, it wasn’t that dangerous. The risks depended a lot on which jobs you were doing. Clerical roles, for example, were quite safe. But the more manual tasks were more hazardous.

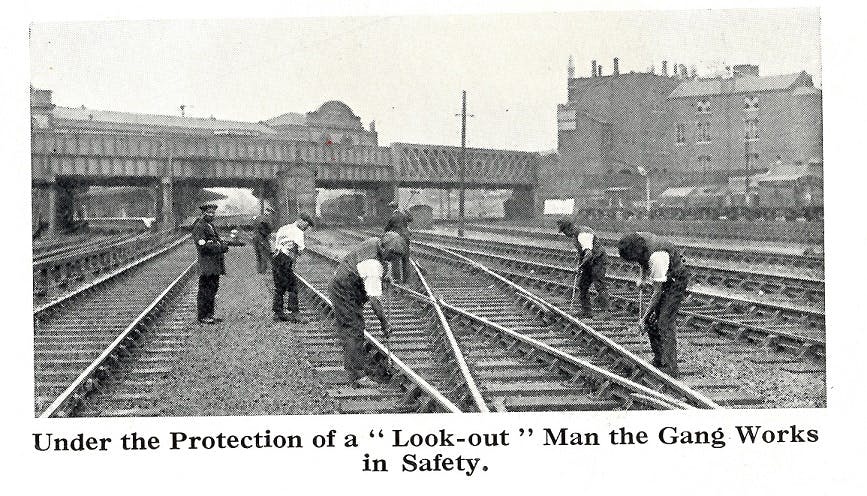

Staff built engines, carriages and wagons and most things the railways needed to operate. They had to maintain the tracks and service and operate the stock. Very often that meant being around moving machinery. Track staff did their work in amongst moving trains. Shunters coupled and uncoupled wagons as they moved. This was heavy, hard work.

A track maintenance gang at work near Paddington in the 1920s.

This also affected who had accidents. Whilst thousands of women were employed on the railways before the First World War, generally, they were in jobs that were less physically demanding (following social conventions of the day).

Put simply, there was relatively little protection for some workers. The railway companies were interested in making a profit and the British state didn’t want to introduce regulation. The industry relied upon things like persuasive posters and booklets to impart safe working practices, something explored in this online exhibit from the National Railway Museum. The trades unions did what they could but until deep into the 20th century, for many employees, railway working remained physically hard and risky.

Railway Work, Life & Death

The Railway Work, Life & Death project is making it easier for you to find out about the working lives and accidents of your railway ancestors. We’re taking unindexed records currently only available in person at archives and volunteer teams are transcribing them. We’re then making the details available on our website.

The unique project is a collaboration between the University of Portsmouth, National Railway Museum and Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick. We’re also working with The National Archives. None of this would be possible without the brilliant volunteers at each institution, so we’d like to recognise them and offer our sincere thanks.

We’re working towards making available details of about 70,000 British and Irish railway worker accidents, from the late 1880s to 1939. So far we’ve got about 6,500 cases publicly available with more to come.

There are three main types records we’re transcribing;

- Accident reports produced by state officials after 1900

- The records kept by the railway companies themselves

- Records kept by the main railway trade union, the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (after 1913, the National Union of Railwaymen; now the RMT).

Between them, they reveal so much about who was involved and what happened. Names, dates, ages, locations, details of the working practices and the accidents, changes that happened afterwards, the families affected. We can see the individuals involved but also put them in context, and gauge how common the accidents were.

We publish weekly blog posts on our website which discusses the accidents, railway work and the people involved. Our Twitter account also provides plenty of material. We want to try to give a wider railway context and make technical detail accessible.

The bigger picture

One of the really valuable things our work does is enable connections between different records. Before, if you’d wanted to check railway company, trade union and state accident records, you’d need to have visited at least two different archives and taken a chance searching unindexed volumes. Our project brings these sources together, making it easier to find the details you want.

Take the case of George Player. He appears in all three of the record types we’re making more easily searchable. From the state accident record, we learn that on 11 March 1911 he died in an accident on the Cardiff Railway. He was a coal tipper and weigher and while on duty was swept off his feet by a capstan rope, meaning he fell under some passing wagons. The Cardiff Railway Company was asked to improve the working environment – which it seems to have done. From the Company’s accident register, we learn that George lived at 22 Byron Street. After the accident he lived long enough to reach the infirmary; the inquest found the death to be accidental.

From the trade union records, we learn that George was 36 when he died and had joined the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants on 29 March 1908. He had three children under 14. His widow received five shillings per week from the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants’ orphan fund for their care. She also received £268.15.7 compensation, from the railway company.

And of course, Findmypast can help unlock more of the story. The digitised railway trades union membership registers give more detail about some of the staff who had accidents. Contemporary newspapers often provide fulsome (if sometimes graphic) accounts of coroner’s inquests. They can be worth exploring even if your railway ancestor wasn’t killed in an accident. Sometimes they can appear as a witness in another case, giving you the actual words they spoke at the inquest.

Physical connections

Sometimes it’s possible to make very tangible connections to the people who had accidents. On the cover of a 1961 accident prevention booklet the owner has added his name: R Eggaford.

1961 accident prevention booklet for signal and telegraph staff.

Is this the Robert Durwood Leslie Eggaford who appears in the accident records in 1927? We can’t say for sure, but he’s a good fit. He was 27 at the time of his accident, so likely to be working aged 61. He was also working in the right kind of job to receive the 1961 booklet.

In the accident, on 15 October 1927, he was working on the railway lines near Briton Ferry Road, in Swansea. With him was a colleague, Alfred Chilham Miller, age 48. A train caught them unawares (surprisingly easy to happen), killing Miller but only causing Robert cuts and bruises. This booklet really makes that connection to Robert – we can handle something that he touched.

Collaboration welcome

We really value hearing from people. It’s lovely to see where we’ve helped – and where we learn from you. Our project is great on the railways side of things, as it’s what the leaders know most about. Finding out about the people behind the accidents can be more of a challenge – one which the family history community has shown us it’s more than up to.

Both online and at family history shows, we’ve met inspiring researchers with fascinating family stories. Happily, they’ve been willing to share, and have produced some excellent guest blog posts. A family mystery solved, the life-story of a Welsh one-armed station-master, a case that ended up locating descendants in Australia and plenty more. One of our volunteers, Rosemary Leonard, even found her great grandfather in the first volume of accident records she was transcribing.

We’re always open to guest posts, so if you’ve a railway worker accident in your family past and fancied writing it up, just let us know.

More to come

What does the future hold for Railway Work, Life & Death? Well, our excellent volunteers have been working hard to transcribe lots more individuals’ accidents. We’re currently preparing four new sets of details for release – around 30,000 cases from the 1890s to 1939. And we think there are around 30,000 more cases that they’re working on from various official records. Keep checking our website for updates.

We’re also keen to find ways to go beyond the official railway records. Newspapers and other sources – including personal records, kept by families and descendants of the individuals – really help us understand the people involved. We’d love to find a way to allow people to share those records, matching them up with individuals we’ve already recorded and adding men and women we don’t yet know about.

And we want to hear from you, with the stories behind your railway ancestor’s accident. You can reach us on railwayworkeraccidents@gmail.com or on Twitter @RWLDproject. The more we learn about the men, women and children behind the numbers, the better.

About the author

Dr Mike Esbester is Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Portsmouth. He is one of the co-leaders of the Railway Work, Life & Death project. His research looks at 19th and 20th century Britain, with a particular focus on histories of everyday life, including transport, accidents and safety. He is a keen advocate of the value of collaboration in research, involving as many people as possible from all walks of life in finding out about their pasts.

Related articles recommended for you

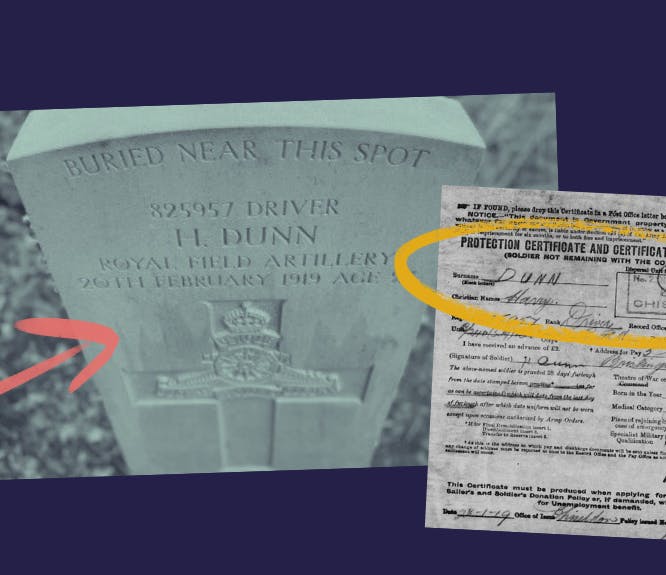

Researching this WW1 grave helped honour a forgotten hero and reunite a family from across the world

Discoveries

How genealogy can bring your family closer

Getting Started

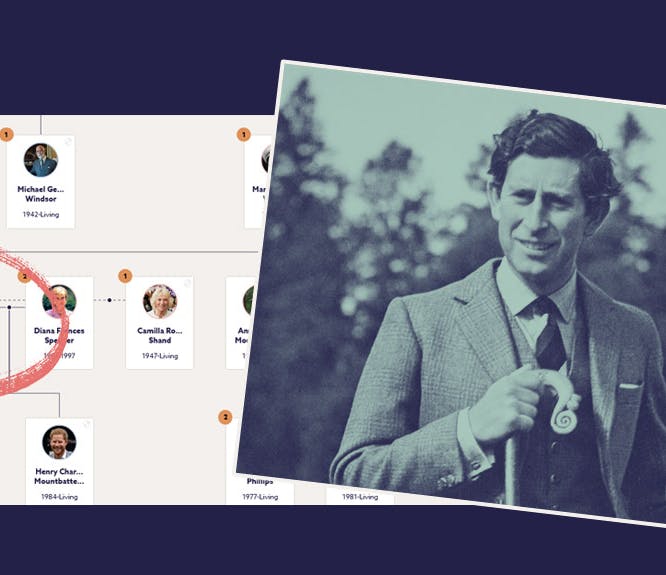

Who's who on King Charles III's family tree?

Build Your Family Tree