The curious history of government-funded British Restaurants in World War 2

8-9 minute read

By Guest Author | June 22, 2020

The UK government’s ‘British Restaurants’ popped up all over the country during World War 2. Professor Deborah Sugg Ryan draws on her research to tell us more.

I delved into the fascinating history of the UK government’s communal British Restaurants for BBC Two’s A House Through Time. In the series, I told the story of Mary and Issac Long who moved into 10 Guinea Street, Bristol, after being bombed out of another house in the road in 1941.

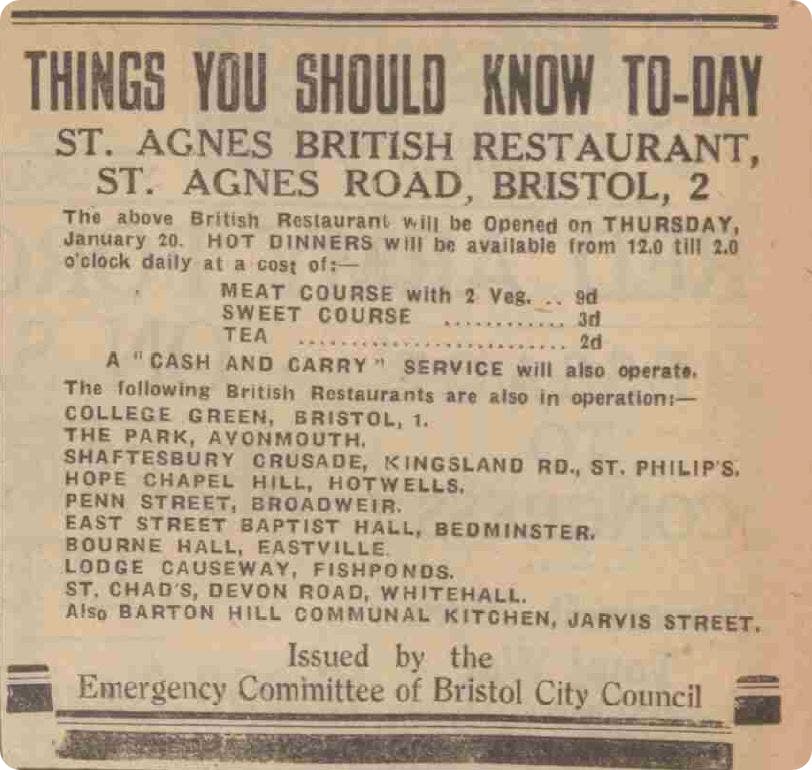

Like many people who had lost their home and had no access to a kitchen, the Longs would have struggled to feed themselves. The solution was a visit to a ‘British Restaurant’, an initiative led by Britain’s Minister of Food Lord Woolton to improve the nation’s health and strength in the war. By 1944, ten different British Restaurants were serving the population of Bristol.

Western Daily Press, 12 January 1944.

Communal feeding centres in the Second World War

On Lord Woolton’s instruction, the Ministry of Food formalized the establishment of ‘communal feeding centres’ in 1940. Also known as ‘community kitchens’, ‘community meal centres’, ‘civic’ or municipal’ restaurants, they had already been established by local authorities and volunteer groups across the country, some of whom had the experience of similar initiatives in the First World War.

Communal feeding centres were originally created to assist the working poor but rapidly gained a broader appeal. For example, to those who did not have access to cooking facilities in their homes because of bomb damage, those who did not have access to a workplace canteen, men affected by the evacuation of women, and women undertaking war work outside the home. Not requiring coupons, they offered people the opportunity to supplement their meagre food rations through the purchase of a nutritionally balanced meal.

Residents of a bombed-out house at Oreston, Plymouth have a break from salvaging belongings from the rubble with a cup of tea and a bite to eat, circa. June 1942. View the full photo.

There was some disquiet over the term ‘communal feeding centre’. Author William Sitwell says that in 1942 Winston Churchill ordered that they should be rebranded. Churchill thought the term was;

""an odious expression, redolent of Communism and the workhouse.""

He told Lord Woolton;

""I suggest you call them British Restaurants. Everybody associates the word 'restaurant' with a good meal." "

In 1943, The Times reported there were over 2,000 British Restaurants, increasing at a rate of ten a week with constituents urging their local authorities to supply more. Approximately 180 million meals a week were taken in catering establishments, with British Restaurants or industrial canteens, representing about ten per cent of the total civilian food supplies.

Making British Restaurants

Most British Restaurants utilized existing buildings such as church halls, town halls, working men’s clubs, schools, hospitals, shops and private houses that were temporarily loaned for the purpose and intended to revert to their original owners and purpose after the war. I filmed the sequence for A House Through Time in St Mary’s Memorial Hall in Woodford, which was used as a British Restaurant. One of our researchers even found a film clip of it from the war.

The spaces that were used for British Restaurants were often less than ideal and there were considerable challenges involved in converting them. The Ministry developed a special ‘Nashcrete’ prefabricated hut that could be erected if there was no other suitable accommodation, one of which was erected at Bristol’s College Green.

The sourcing and layout of furniture proved a challenge to some British Restaurants. Small tables with plenty of room between them were thought to be ideal but some restaurants had no choice other than to use long refectory tables because of the availability of furniture and the need to seat lots of people. Undoubtedly, some British Restaurants simply had to make do with what they had and procure whatever they could find. Other restaurants made an effort with their furniture, painting tables and chairs in bright colours and topping tables with linoleum or ‘American cloth’ and decorating them with vases of flowers and bunting. For some customers, the restaurants proved to have better facilities than those they had at home and many restaurants reported the theft of cutlery.

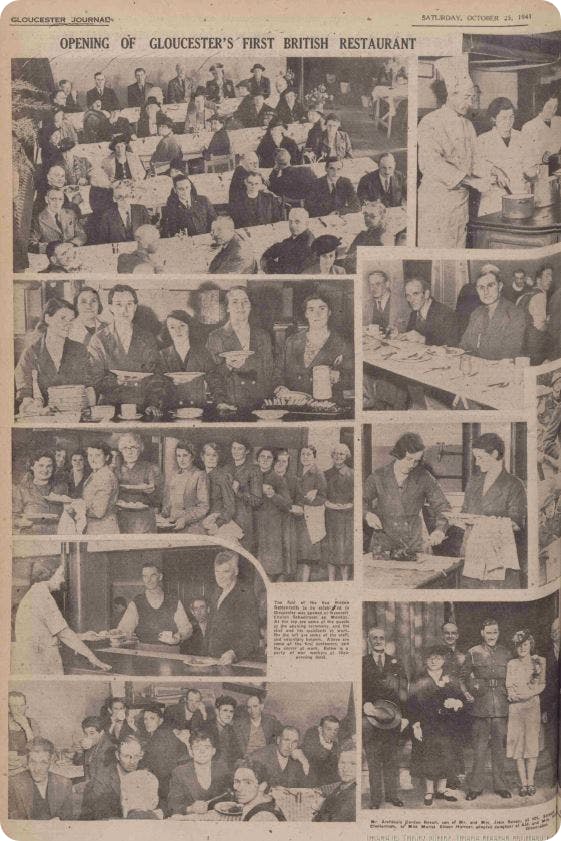

The opening of Goucester’s first British Restaurant, Gloucester Journal, 25 October 1941.

The majority of British Restaurants had a self-serve cafeteria set-up, with customers queuing at a counter, rather than a waitress service. This was partly prompted by the realisation that vitamin C was perishable when food kept for long time in hot containers or plates, leading to reductions in cooking times and practice of serving meals from pot to plate.

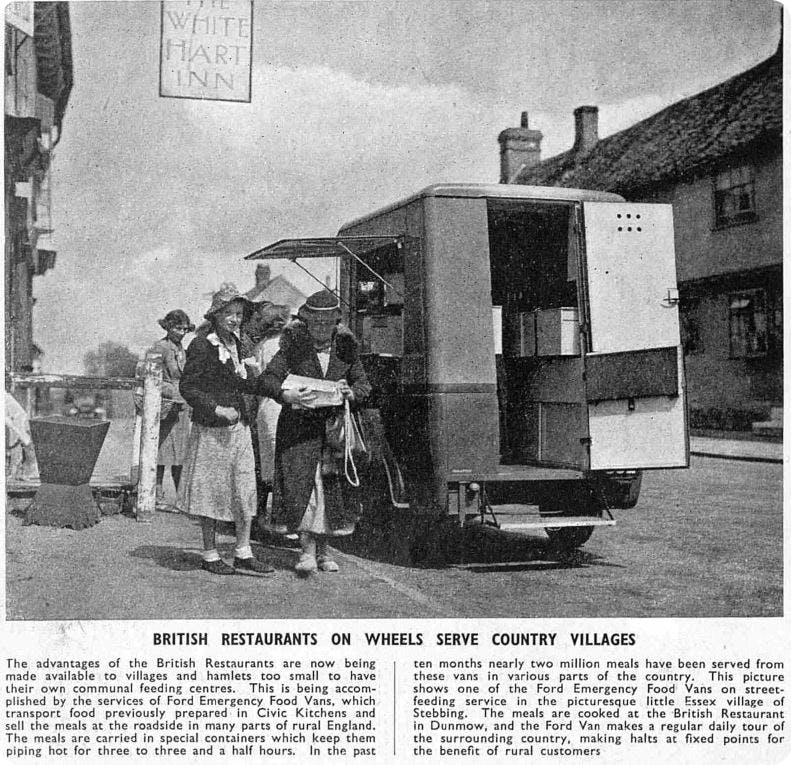

Most British Restaurants had a ‘cash and carry service’ where customers could buy food and take it away in their own receptacles to consume it at home, rather than in a communal dining room. This was a boon to the poorest who could stretch out the portions. Food coupons were not required. Customers paid in cash for a ticket or token, then queued up and exchanged that for a dish. British Restaurants and other organisations also ran mobile canteens that could be sent out to bombsites. In rural areas, a ‘pie scheme’ was offered coordinated by the Women's Voluntary Services (WVS).

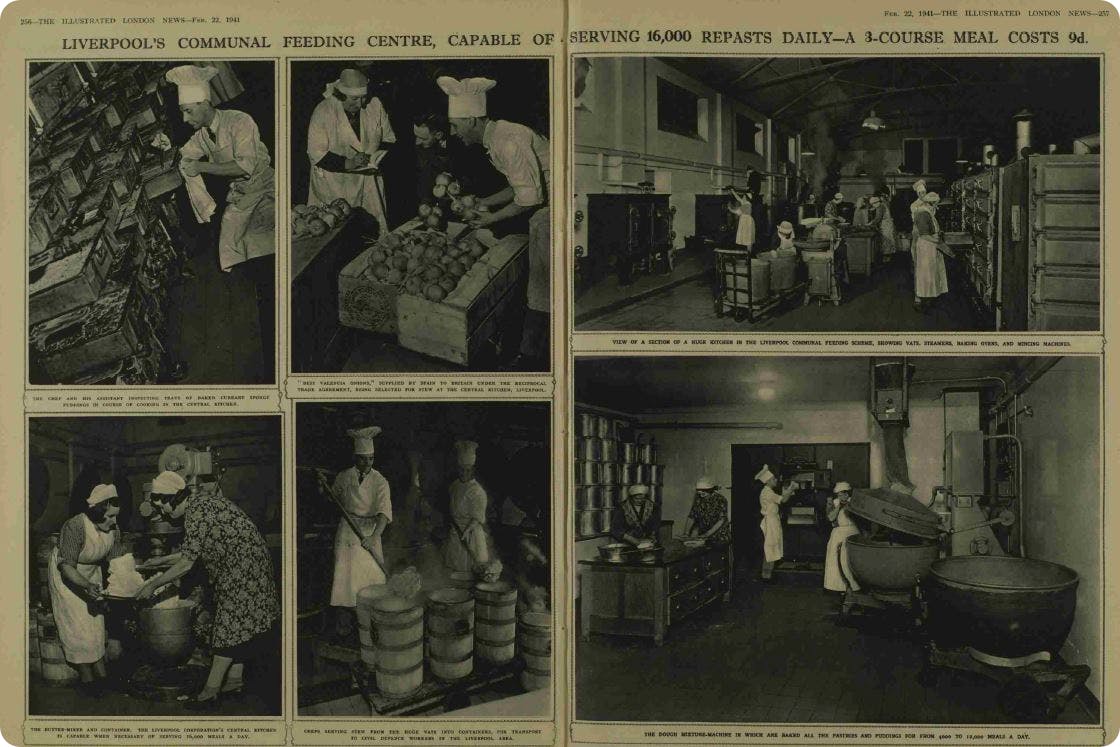

Local councils were expected to supply the venues for British Restaurants and the people to run them. About a third of British Restaurants were supplied with meals from central kitchens run by the Ministry of Food or local authorities; the rest had their own kitchens. The Government supplied the equipment and fittings. Kitchens proved a particular challenge as space was often cramped and the ensuing layout of equipment was inconvenient and overcrowded. British Restaurants were expected to be fully self-supporting and cover repayment of capital expenses over eight and a half years and any profit was taken by the Ministry.

About a third of British Restaurants were staffed by volunteers from the Women’s Volunteer Service but it was thought desirable to pay the minimum wage so that they did not undercut private restaurants. Many of these were middle and upper-middle-class women unused to doing their own cooking. The use of unfamiliar professional kitchen equipment posed challenges to them. At this time, many did not have fridges in their own homes let alone electric ‘labour-saving’ appliances. They struggled to fulfil the demands of mass catering, exacerbated by restricted or unfamiliar ingredients and equipment. These challenges are brought to life in Caroline Beecham’s novel Maggie’s Kitchen, which describes the setting up and running of a British Restaurant.

Illustrated London News, 22 February 1941.

A good meal

A series of surveys on the nutritional adequacy of what was served shaped the planning of meals and menus by the Ministry’s Food Advice Division. Ingredients were supplied centrally through the Ministry of Food, supplemented by local donations.

Some restaurants grew their own food, converting their grounds into allotments. The three-course meals served in the middle of the day were familiar British comfort food. They typically consisted of soup followed by a meat, fish or vegetarian main course accompanied by potatoes and other vegetables, followed by pudding and tea and coffee.

What was Woolton Pie?

The limitations of the wartime food supply meant that people had to try some unfamiliar foods, which lacked visual appeal as well as taste. As the meat supply became scarce, there was a concerted effort to persuade people to eat more vegetables. The Ministry created Woolton pie, which made a virtue of vegetables. It contained diced and cooked potatoes, cauliflower, swede, carrots, spring onion, vegetable extract if possible, and a tablespoon of oatmeal. The vegetables were cooked and cooled, placed in a pie dish sprinkled with chopped parsley and covered with a crust of potatoes or wholemeal pastry. It was served hot with brown gravy. It was unveiled at the Savoy and appeared on the menu of British Restaurants.

Sunday Mirror, 12 October 1941.

Byrom Restaurant, Liverpool

One of the earliest self-supporting and non-profit-making communal restaurants outside London in the Second World War was Byrom Restaurant in Liverpool, opened on 11 November 1940 by Lord Woolton who came from the city. Byrom Restaurant was a conversion of four empty lock-up shops with four floors of flats above, integrated into a tenement scheme. The restaurant had a large kitchen with both electric and gas appliances and the professional equipment needed to produce large numbers of meals.

Byrom Restaurant was a spacious and pleasant environment for customers with a cream, green, blue and red paint scheme and patterned flooring, lit by large glass globes suspended from the ceiling. This was an interior scheme that had really been thought through. The vast walls called for bold decoration. This was provided in the form of murals executed by Tom Mellor, a young architectural assistant in Liverpool’s housing department. The Liverpool Echo said the murals;

" "set the keynote of bright cheerfulness.""

Byrom Restaurant became the Ministry’s showcase and it was promoted in a propaganda film hosted by comedian Tommy Trinder, encouraging people to eat at British Restaurants.

The Liverpool Daily Post reported that the writer J.B. Priestley visited the restaurant and praised it for its

""clean, bright and sensible appearance...with a special word of praise for its murals in a broadcast talk.""

Brighter British Restaurants

Not many establishments were as well designed as the Byrom Restaurant with its spaciousness and cheerful décor, and attention to the flow and comfort of its customers. Many resembled a work's canteen. Lady Elizabeth Clark, wife of the eminent art historian and director of the National Gallery Sir Kenneth Clark, ran a campaign to improve the surroundings of the restaurants in London. She borrowed art from national collections, including Buckingham Palace, commissioned prints of famous paintings and got artists and students to undertake murals.

This romantic landscape, which was hung in the new “Churchill” British Restaurant at Ilford, was lent from Buckingham Place by the King. The Sketch, 10 March 1943.

In 1943, Lord Woolton said that he wanted ‘brighter’ British Restaurants. He claimed that the most attractive ones, with walls decorated with pictures or murals of local history, made the best profits. Moreover, the Daily Mail reported he said;

""it has been proved that art is an aid to appetite.""

The Ministry of Food developed a decoration policy to make British Restaurants more attractive to customers. The policy specified ideal layouts, bright colour schemes and furnishings to create a morale-boosting, cheerful atmosphere. Clive Gardiner, a poster designer, illustrator and muralist, and Principal of Goldsmith’s College of Art, was employed to offer advice to local authorities on questions of design and interior decoration. He commissioned lithographs and posters from contemporary artists and continued the murals initiative begun by Lady Clark.

Eating out

Only a small proportion of those who frequented British Restaurants were normally customers of commercial establishments. The majority were people who had either taken sandwiches to work or gone home for meals and now lacked proper cooking conditions and someone to cook. For many customers, British Restaurants were their first experience of dining outside the home. Even those who could afford to eat out in restaurants and cafes had not done so before because of the sanctity of the privacy of home and long-held taboos about eating in public.

Despite being very popular with the public, British Restaurants were officially disbanded in 1947 when there were still 1,850 of them. The Government withdrawal of financial responsibility for communal feeding led to the gradual ending of the scheme. Some converted to civic restaurants run by local councils and continued to operate until the mid-1950s. You will soon be able to visit a recreation of the Dudley Civic Restaurant at the Black Country Living Museum as part of their new 1940s-60s town.

In short, the UK's wartime British Restaurants provided affordable and nutritious food in pleasant and sociable spaces. They permanently accustomed many workers to take their midday meal near their place of work rather than returning home and brought eating out to the masses.

Do you have family stories about British Restaurants? Perhaps you have a memento such as one of the Bakelite tokens used to pay for meals. We'd love to hear what you've discovered. Reach out to us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter using #WhereWillYourPastTakeYou?

About the author

Deborah Sugg Ryan is Professor of Design History at the Faculty of Creative and Cultural Industries (CCI), University of Portsmouth. She is a consultant on all 3 series of BBC Two’s A House Through Time, as well as being an expert onscreen contributor. Her other television appearances include Inside the Factory, David Jason's History of British Inventions, and Number 57: The History of A House. She has also worked for the V&A Museum as a curator and advisor. Deborah's most recent book is Ideal Homes: Uncovering the History and Design of the Interwar House (Manchester University Press, 2020) which was awarded the 2020 Historians of British Art Book Award for Exemplary Scholarship on the Period after 1800. She is currently writing a book about the history of the kitchen and is working with the Science Museum (London) on a project on the history of domestic appliances.

Further reading

- Peter J. Atkins, 'Communal feeding in wartime: British restaurants, 1940-1947.', in Food and War in Twentieth-Century Europe (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011, pp. 139-153)

- Simon Briercliffe, BCLM: Forging Ahead: Building a new urban history of the Black Country. Urban History (2020, 1-17)

- Nadja Durbach, Many Mouths: The Politics of Food in Britain from the Workhouse to the Welfare State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020)

- Bryce Evans ‘The National Kitchen in Britain, 1917–1919’, Journal of War & Culture Studies, (10:2, 2017, 115-129)

- William Sitwell, Eggs or Anarchy: The remarkable story of the Man Tasked with the Impossible: To Feed a Nation (London: Simon and Schuster, 2016)

Related articles recommended for you

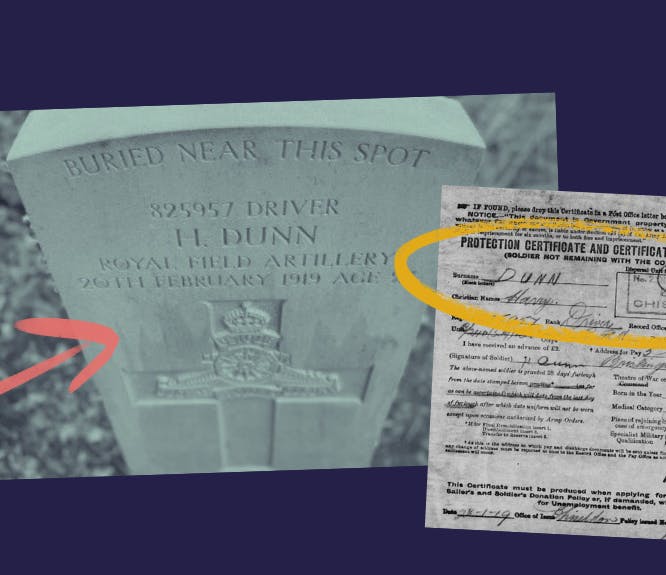

Researching this WW1 grave helped honour a forgotten hero and reunite a family from across the world

Discoveries

Everything you need to know about importing and exporting family tree GEDCOM files

Build Your Family Tree

The incredible true story behind The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare

History Hub