The vibrant Black history of Notting Hill Carnival

4-5 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | August 4, 2022

In its 60 year history, Notting Hill Carnival has become a symbol of Black Britain and its resilience to celebrate cultural pride in the face of oppression and discrimination.

Once used to target the Black community and tarnish Afro-Caribbean culture, Notting Hill Carnival has become a national British icon, honouring multiculturalism and the uniting of diverse identities across London and the UK. However, the origin of Notting Hill Carnival will always be in the Caribbean and with London’s Black British community.

It's difficult to comprehend the modern Notting Hill Carnival in the context of the 1950s. Race relations in the post-Windrush UK were appalling and further deteriorating. The Racism the newly-formed Caribbean-British community experienced was rampant and it came to a head in 1958.

The Notting Hill race riots

Racially motivated violence on Black Londoners occurred throughout the summer and culminated in the Notting Hill race riots. On 29 September, a mob of white nationalists marched on Bramley Road and attacked the homes of the West Indian residents. The riots continued every night until 5 October.

When did Notting Hill Carnival start?

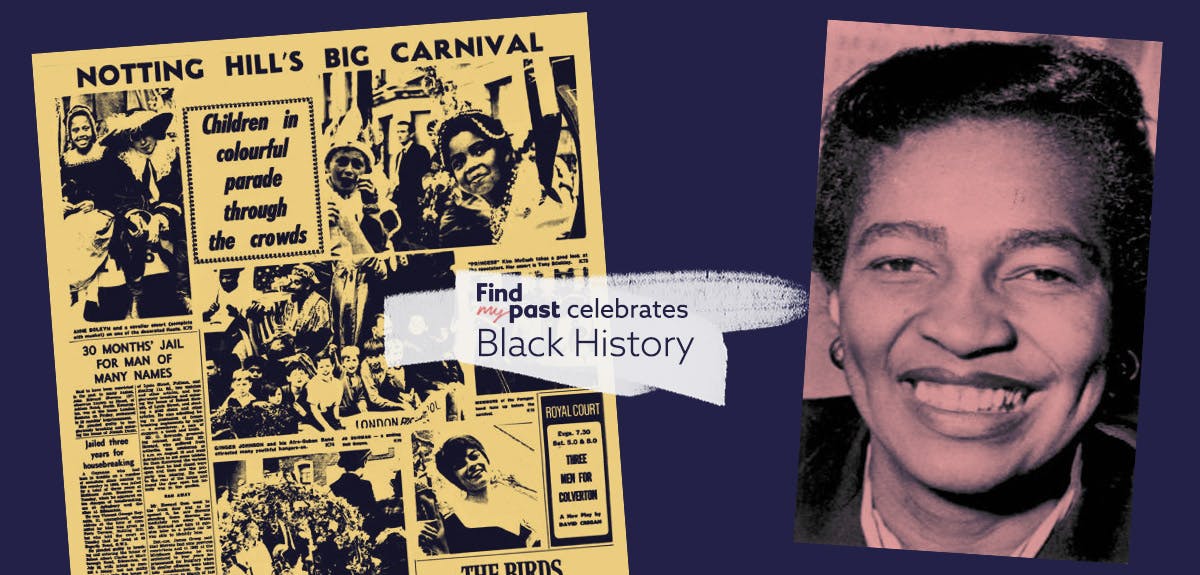

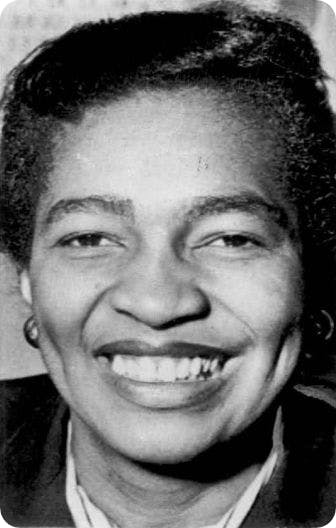

As a social response to the riots, the first Notting Hill Carnival took place the following January in the form of an indoor, BBC televised event at St Pancras Town Hall. The founder of the Notting Hill Carnival was Claudia Jones, a Trinidadian journalist and activist, who worked closely with fellow Trinidadian and influential musician Edric Connor. Connor became a regular performer over the early years of the carnival and Jones is now known as the ‘Mother of Notting Hill Carnival’.

Claudia Jones, 1915-1964.

This first Notting Hill Carnival showcased elements of Caribbean culture and art, taking inspiration from the original carnivals of the Caribbean islands but presented in a more European cabaret style. There is some debate as to whether this event was really the first Carnival, but most agree on its importance in the Carnival's history and the UK’s Caribbean community.

Over the next few years, the Carnival took place in this format, however another event that more closely resembles today's extravaganza was being planned. Rhaune Laslett from Stepney was the President of the London Free School, a group of activists and emerging artists based in London. The group, led by Laslett, wanted to establish a festival to bring together the various ethnic groups and nationalities in the then-disadvantaged area of Notting Hill. Laslett felt that;

""although West Indians, Africans, Irish and many other nationalities all live in a very congested area, there is very little communication between us.""

She wanted to change this whilst also challenging the perception that Notting Hill was a run-down slum area, something that’s hard to imagine now, partly due to the success of the Carnival.

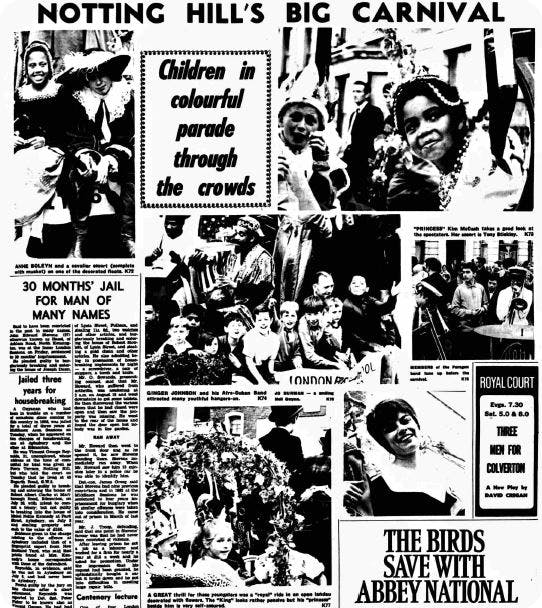

The London Free School realised their dream of a community fair for Notting Hill in September 1966. Originally a traditionally British fair, the various identities and ethnicities of the Notting Hill area were given the chance to showcase their culture and interact with others. It's safe to say, over 50 years on, their more lofty goal of cultural unity has been largely achieved.

Kensington Post, 23 September 1966. Read the full article.

The 1966 Notting Hill Carnival hosted famed Trinidadian musician Russell Henderson, who had previously performed at the indoor edition. Henderson’s influence, as well as other musicians who performed in the first few years, shaped the event into what it is today. He moved off the stage and into a precession to bring more energy and excitement. This was a driving force behind the two iterations of the Carnival merging - and why today it epitomises West Indian carnival culture.

The fair continued annually and by the late 1970s it was undeniably Caribbean, and only growing in popularity. In the 10 years after its inception, the Carnival progressed from two bands to a dozen and, after operating out of The Mangrove Restaurant for a time, it attracted sponsorships, introduced generators and sound systems, and the route was extended.

The origins of Notting Hill Carnival costumes

Most of these advancements were credited to Leslie Palmer, Notting Hill Carnival's director from 1973 to 1975. Palmer encouraged bands, performers and attendees to wear traditional masquerade costumes, a Caribbean tradition that goes back hundreds of years. Enslaved Africans on the British and French West Indian plantations would hold their own festivities when their masters held masquerade balls for lent.

The enslaved would mimic the costumes worn by the Europeans as a way to mock them. After emancipation, these costumes became a symbol of freedom and cultural identity, traditions that survived over two centuries, made it back across the Atlantic with the Windrush Generation, all the way to Notting Hill. By the mid-1970s, the Notting Hill Carnival of today was beginning to take shape, but unfortunately, racist attitudes of the time would still have to be confronted.

Racism, tension and clashes

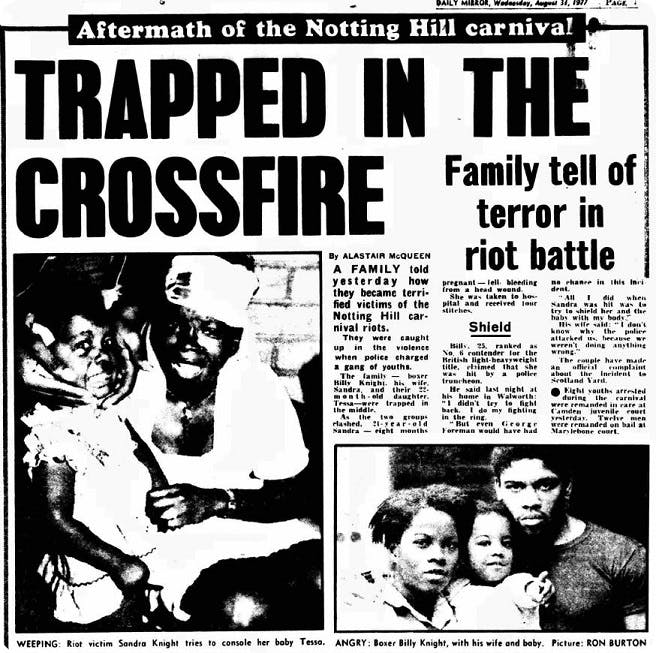

The more West Indian the Notting Hill Carnival became, the more it seemed to spark racial tensions and be tarnished by riots. In reality, the Carnival was an easy and large-scale target for those who wanted to harass London's Black British communities. The policing of the Carnival at this time was harsh and uncompromising. Media coverage was overwhelmingly negative and one-sided, often portraying the Carnival as menacing and attendees as troublemakers.

Daily Mirror, 31 August 1977. Read the full article.

Disproportionate coverage of confrontations at the Carnival put tensions on a knife edge every year. Huge numbers of police violently broke up the predominantly Black crowd in 1976, resulting in rioting and arrests. Whilst the violence did slowly diminish as the years went on, it wasn’t until 1987 that the approach to policing the Carnival softened in response to the clashes of that year.

For the first time in 54 years, the Carnival was forced to desert the streets of Notting Hill in 2020 and 2021 due to the Coronavirus pandemic. The organisers replaced in-person festivities with online events. However, the previous few years attracted around one million attendees, making it the largest street party in Europe. The tribute to Caribbean, African and Black diasporic culture has stayed true to its roots through its unmistakable sounds, colours and atmosphere.

The spectacle of the modern Carnival however has changed, its significance is now far beyond the cultural unity of the Notting Hill area. The Carnival is part of the identity of the UK’s Afro-Caribbean community, a symbol of their fight for equality, a huge event in the British calendar and a £93m contributor to the UK economy. The Notting Hill Carnival is one of many ways Black people have made a profound cultural impact on Britain, and perhaps the most fun.

Related articles recommended for you

Episode guide: A House Through Time series five

Discoveries

Irish genealogy deep-dive: Discover the remarkably rich Irish family history behind Irish diaspora through the centuries

Help Hub

The painstaking process of preserving old family records

Family Records