10 ways to find out what your house was like generations ago

10+ minute read

By Guest Author | January 20, 2022

Professor Deborah Sugg Ryan from BBC’s A House Through Time explains how to discover what your house looked like when it was first built and beyond.

If you’ve ever wondered, “how to find the history of my house”, the first question you might have asked is “who lived in my house?” But what can you do next? What about the house itself?

You might want to find out more about what your house looked like years ago and what life might have been like in it. Here are my top ten tips to help get you started.

1. Examine house deeds and plans

You might be lucky to have plans and blueprints for your house documenting its original interior layout. These might include drawings of the exterior and even interior details such as fireplaces. Sometimes these are deposited in local archives.

Local authority planning records, which are often available online, can help you understand changes made to your house. For example, when I lived in a small semi-detached house built in 1934, that I discuss in my book on the interwar home, I discovered that my kitchen extension was added in 1948 and called a ‘scullery’ in the application, which also gave me insights into its use.

The kitchen in Deborah's 1930's house.

If you live in a listed house in England, you can read the original listing in the National Heritage List for England (NHLE). This was a very useful source for us in A House Through Time when discovering more about Bristol’s number 10 Guinea Street as it told us about its architecture and interiors.

Similar lists are available for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

2. Look at your house closely

If you have access to the house you’re researching, take a good look around you. You might be lucky to find a date inscribed on the front of the building, as is the case with 10 Guinea Street, Bristol, which has its date – 1718 – on a keystone on the facade.

No. 10 Guinea Street, Bristol, the house featured on series three of A House Through Time. Credit: BBC/Twenty Twenty Productions.

Look for original features. These include windows, doors, moulded plasterwork, ceiling roses and fireplaces. These will help you date the house. Layers of wallpaper often give you a fascinating glimpse of the changing décor of your house through time.

Be aware that in larger terraced houses in the 18th and 19th centuries the main reception room was often upstairs at the front of the house. It was usually the biggest room in the house, running right across its width, with the largest windows and the grandest fireplace.

In smaller houses it was common to keep the front reception room on the ground floor as a parlour for “best” well into the 20th century. People tended to live in the rear reception room, often cooking in there as well, with a small rear scullery for “dirty” work such as washing up and laundry.

Ideal Homes: Uncovering the History and Design of the Interwar House. Order here.

Keep an eye out for any building alterations necessitated from modernisation such as the installation of bathrooms. Often rooms were divided into two. You might also find extensions or separate buildings that originally housed a W.C., which have now been repurposed for other uses.

In the 18th century, kitchens were sometimes in separate blocks to minimise the risk of fire and smells. Our investigations into Bristol’s 10 Guinea Street concluded that this was the case. In the 19th century, kitchens could often be found in basements but were commonly moved into a rear reception room in the ground floor in the 20th century when domestic service went into decline.

Maps can help you work out the changing footprint of your house. If you can’t access the house that you’re researching, look it up on Google Street View. You might also find estate agents' details for when the house (or a similar one nearby) was sold. These usually include photographs, which may include original features, and floor plans.

3. Examine census records for signs of multiple occupation, the number of occupants and rooms

An address search will find who lived in your house, but it can also tell you so much more about how the interior of your house might have looked and been used. The 1911 Census and 1921 Census record separate households at the same address as separate entries, revealing houses in multiple occupation or divided into flats.

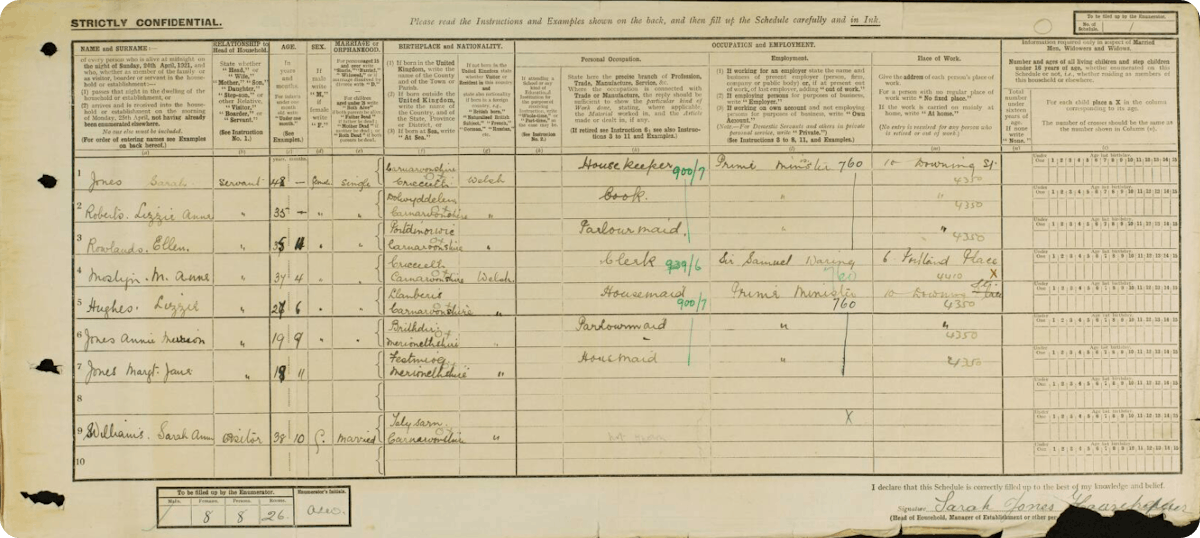

The 1911 Census and 1921 Census also tell you how many people lived in each household of your house and how many rooms they occupied. This information can be found on the original image, like this one.

10, Downing Street in the 1921 Census for England and Wales.

In the 1911 Census, a box records the total numbers of males, females, and persons, filled in by the enumerator. A separate box records the number of rooms in the dwelling (house, tenement, or apartment), filled in by the head of the household. In the 1921 Census, this information is combined in one box, and both were entered by the enumerator to ensure greater accuracy. So, you may spot discrepancies in the total number of rooms between census years: the information may not have been recorded accurately, or the layout of the house may have changed.

The kitchen was counted as a room, but not the scullery, lobby, closet or bathroom and any warehouses, offices or shops that were part of the property. The term “scullery” caused confusion in some parts of the country, as it had the same meaning as “kitchen”. It was only recorded as a separate room if meals were taken in it.

In a house of multiple occupation, especially where households occupied only one room, some facilities like sculleries may have been shared, or there may have been makeshift arrangements like cookers on landings. It was common for rooms to be accessed via another separate room, rather than through a corridor, meaning that households weren’t self-contained and there was little privacy.

In the 1921 Census, don’t assume that a better off household living in spacious circumstances with lots of rooms no longer has any servants. There was a shift towards servants living out, which you will see reflected in the Census. For example, you might find a listing for a servant with employer listed as “private” and place of work giving a different address to where she is living.

4. Rifle through family heirlooms

Items of furniture, ornaments and other objects might have been passed on through your family. These can give you a great idea about the décor and furnishing of your house.

Wills and probate records can be incredibly useful if they include a list of contents. We found a probate record for one of the neighbouring Guinea Street houses to number 10 and it brought to life how our house might have looked.

5. Talk to your relatives and neighbours

Ask others about their memories of the house. The Oral History Society has some great advice on how to do interviews.

If you have any old family photos, or objects passed down as heirlooms, they can be great prompts when doing interviews with family members.

When I lived in my 1934 semi, I got to know a very elderly neighbour up the road whose house had escaped modernisation. I discovered when I visited that he lived and cooked in his rear reception room that had a sink in one alcove and a cooker in the other. This led me to realise that my small lean-to kitchen was a later extension.

6. Gather old photos of your house

Relatives and neighbours might have family photographs taken indoors but be aware that it was not common for amateur photographers to use flash until the post-war period, so you are often more likely to find photos of the exterior of the house or the garden.

For ideas of what your house or its residents or the place in which it was located might have looked like you can search through thousands of snapshots in the Findmypast Photo Collection.

A photo of Miss Stella Silk in her 1950's kitchen, found in the Findmypast Photo Collection.

Historic England has collections of photos of the exterior and interior of houses. Photos often accompany records of houses that have been listed.

RIBA is another great source, especially if your house was designed by an architect.

John Boughton’s Municipal Dreams blog is a wonderful source of photos and information on social housing built by local authorities.

Many regional museums and archives have collections of photographs where you might find a photo of your street.

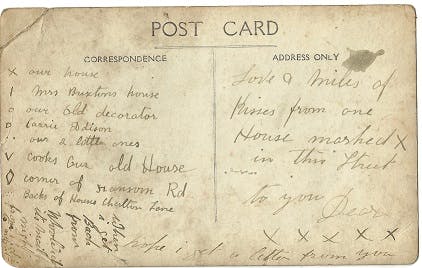

Old postcards are great sources of information on houses. They are often available in local museums and archives and can be purchased cheaply. I have a postcard that my great grandfather Will Lacey sent to my great grandmother Edie Wimbury while they were courting. It shows the street that they both lived in with their respective families as next-door neighbours, annotated with useful information.

The postcard exchanged by Deborah's great grandparents, including an "x" marking the location of her great grandfather's house.

TuckDB Postcards is a free database of antique postcards published by Raphael Tuck & Sons that can be searched by place.

7. Peruse archive film footage

Films can be great sources for seeing the history of houses and interiors. You might be lucky enough to have old family cine films or your house might have starred in a feature film or a television drama. When I was a PhD student, a neighbour told me that the flat I lived in had been used in the film The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner.

News features often reported on new developments built by local authorities. See British Pathé, Huntley Film Archives and the British Film Institute.

The British Universities Film and Video Council website is a useful portal for searching for moving image content and sound collections from across the UK.

8. Visit historic houses and room sets

During the making of A House Through Time, I’ve filmed at many houses open to the public. Some are owned by the National Trust or English Heritage but there are others that are independent. I’ve also filmed at living history museums that have the advantage of containing many houses of different types and periods.

Deborah recording an episode of A House Through Time at Beamish. Credit: BBC/Twenty Twenty Productions.

Be aware that it was unusual for people in real life to have décor and furniture all from the same decade. It was common for people to invest in furniture at the point of marriage and expect it to last, despite fashions changing, and there’s long been a market for antique and second-hand furniture. However, textiles, floor and wall coverings tend to be updated more frequently. Electrical domestic appliances were expensive and not widely used until the postwar period, except for irons and curling tongs. Here are some examples of historic houses and room sets used in all four series of A House Through Time.

- Dennis Severs House, London - In the drawing-room, I told the story of Hester Holbrook, wife of a wealthy trader, and how she entertained her friends with tea parties at 10 Guinea Street, Bristol, in the 1750s.

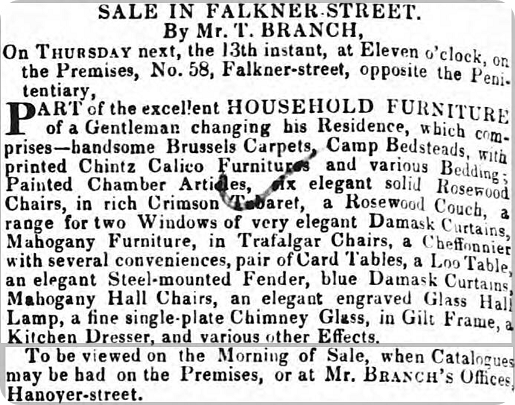

- The 1830s room at the Museum of the Home in London - drawing on a list of contents sold by auction in 1844 from a newspaper advertisement, I discussed the furniture owned by Richard Glenton who worked for HM Customs as a clerk and lived at 62 Falkner Street, Liverpool.

- Charles Dickens Museum - I used this as an example of a Victorian middle-class house, not because of its association with Dickens. In the kitchen, I discussed the experiences of Mary Alder, who kept house for her brother, the amateur naturalist Joshua, at 5 Ravensworth Terrace, Newcastle, in the 1840s.

- Beamish - I told two stories related to 5 Ravensworth Terrace, Newcastle-on-Tyne. I filmed in the drapery shop to talk about Mary Oram, who ran one in the 1890s, which was accessed through the house’s yard. I also used one of the houses in the 1900s town to discuss the experiences of Rose McQueeney who ran number 5 as a boarding house for young Irish men from 1911

- Black Country Living Museum - Using one of the back-to-backs staged in the 1920s, and drawing on evidence from adverts for rooms to let in the local paper, I discussed how 62 Falkner Street might have looked in the 1930s when Robert and Sarah Duffy took in lodgers.

- Moorside House, Bradford Industrial Museum – I discussed how Ann Dawson, who started life in humble circumstances working in a cotton mill, furnished her home as wife of a wealthy cloth finisher in the 1860s.

- Sambourne House – I used the bedroom to tell the story of Mary Mellish’s pregnancy and confinement in the 1870s.

- The Hardmans’ House – I explored Rita Wood’s experience of sharing home with strangers in 1944 and how she might have created a separate flat with a makeshift kitchen.

9. Explore museums and archives

Look for examples of furniture, furnishings, décor, objects and trade catalogues in museums and archives. Many have great websites with a ‘search the collections’ facility.

- The V&A, the National Museum of Scotland, National Museum of Wales and National Museums of Northern Ireland have fantastic collections of all kinds of design that could be found in the home.

- The Science Museum Group website (Science Museum, Science and Industry Museum, National Science and Media Museum, National Railway Museum and Locomotion) has collections of domestic technology.

- Examples of wallpaper, furniture and other trade catalogues and estate agents’ and builders’ and building societies’ ephemera can be found the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture which has an excellent website. I used its Second World War utility furniture scheme catalogue to discuss the experiences of John and Beryl Quayles on A House Through Time.

- The Whitworth Art Gallery (Manchester) has an extensive collection of textiles and wallpaper

- Many other regional museums and archives have excellent collections relating to the design of the home.

10. Scour old newspapers, magazines and domestic advice manuals

Local newspapers often contain advertisements for houses for sale with detailed descriptions of rooms. Try entering your street name. You might even find a list of house contents for sale or auction, like we did for 62 Falkner Street in A House Through Time.

Adverts for rooms to rent can help you understand the layout of a house when it was in occupied by multiple people. For example, it might list two rooms plus a kitchen for rent in a house that you know had more rooms in total than this. For middle-class households, you might find adverts seeking domestic servants, while adverts for shops and products can give you a sense of what the interior of your house might have looked like.

Articles in newspapers, interiors, homemaking and women’s magazines and domestic advice manuals from the period you’re investigating are good sources of contextual visual evidence. Although be aware that these often present the ideal rather than the actual ways in which people lived.

All of these sources can really help you bring the history of your house to life. We'd love to hear what you've discovered about your home. Reach out to us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter using #WhereWillYourPastTakeYou?

About the author

Deborah Sugg Ryan is Professor of Design History at University of Portsmouth. She is a consultant on all four series of BBC Two’s A House Through Time, as well as being an expert onscreen contributor. Her other television appearances include Inside the Factory, David Jason's History of British Inventions, and Number 57: The History of A House. She has also worked for the V&A Museum as a curator and advisor. Deborah's most recent book is Ideal Homes: Uncovering the History and Design of the Interwar House (Manchester University Press, 2020) which was awarded the 2020 Historians of British Art Book Award for Exemplary Scholarship on the Period after 1800. She is currently writing a book about the history of the kitchen and is working with the Science Museum (London) on a project on the history of domestic appliances. Photo © Helen Yates

Related articles recommended for you

'Their hunger will not allow them to continue': the victorious London dockers' strike of 1889

History Hub

Winston Churchill's life story, told through historical records

Discoveries

We found naval officers and aristocrats within Miranda Hart's family tree

Discoveries