Celebrating Black British History: why we’re remembering Black British firsts

4-5 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | May 10, 2024

In a series of articles, Stephen Rigden looks at Black British Firsts – researching and remembering notable achievements in Black history.

It shouldn't have to be Black History Month for us to recognise and uplift stories that are all too often overlooked.

Important books and TV shows like historian David Olusoga's Black and British are shining a light on everything from British Caribbean identity to the role that Black soldiers played in the World Wars, retelling the stories of refugees, enslaved peoples and trailblazers alike.

But what about Black genealogy?

Who was the first Black British Olympian, mayor or voter? Through a series of articles, we're revealing the answers and celebrating these seminal milestones in British history, as told through genealogy:

- Who were the first Black British Army officers?

- Who were the first Black British clergymen?

- Who were the first Black British university students?

- Who were the first Black British mayors?

- Who were the first Black godchildren in the British Royal Family?

- Who was the first Black British Olympian?

- Who was the first Black person bestowed with a British knighthood?

- Who were the first Black British professional footballers?

- Who was the first Black British Air Force pilot?

- Who was the first Black British voter?

Firstly, we ought to provide context and define our terms. The fact is that most of the records created in Britain and used in family history today are silent as to colour, race and ethnicity. Census returns never asked for these details. They were regarded as irrelevant for most Anglican parish registers and certainly for civil registers of birth, marriage and death.

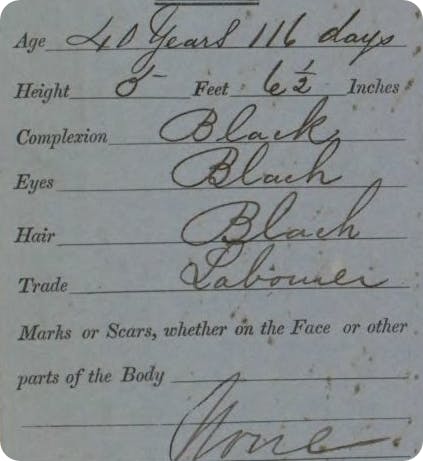

Where such details are recorded, usually it is because they were required for all. For example, some British Army and Royal Navy records include a physical description of the service member – height, hair colour, eyes, complexion and notable features such as tattoos or scars. From the genealogist’s perspective, this is wonderful – we can see that great-great grandfather Stanley was a 5'5" brown-eyed Able Seaman with a tattoo of an anchor on his right bicep and “Nan” on his left.

Black soldier Daniel Adam in our British Army Service Records. View the full record.

This is particularly useful when researching Black history – the physical description helps confirm that the records belong to a Black serviceman and not, for example, to a white person born in Jamaica or the West Coast of Africa during the centuries of Empire.

For several reasons, many Black individuals are indistinguishable from their white counterparts by their names alone. John Adams, James Anderson, Harry Armstrong, George Broomfield, Anthony Burgess…these are names that could be found on any English census return and belong to labourers in Somerset, framework knitters in Nottinghamshire or coal miners in Northumberland. But they are not. In this case, they are the names of impoverished Black people on the streets of London in receipt of financial support from the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor in 1786.

In most family records, you would not know or suspect that James Anderson was Black and therefore it’s invaluable when you do come across a physical description or other markers of Blackness.

For many Black British people, the surviving paper trail may hold only a single record that is evidence of Blackness at all – all the other documents are silent. This is one of the challenges but also satisfactions of researching Black British family history.

It also proves a fundamental rule of genealogical research, that it’s so important to try to flesh out the bones of individuals on your family tree, and not just accumulate the skeleton of names, birth, marriage and death dates.

Where can you find records of Black people in Britain?

As mentioned, armed forces records are great sources. So are crime records. In the age before mass photography, a physical description of a criminal was required, but the same records often involved victims and witnesses.

The detailed court proceedings of London’s Old Bailey are a good example. Another example is that of those too often neglected records at the bottom of the parish chest – the Poor Law examinations, settlements and removals.

Words to watch out for

Historical records use the language of their time. As you explore them, you'll see words that are no longer used and no longer found acceptable. Some of that language was very precise. For example, terms such as 'mulatto', 'quadroon' and 'octoroon', whatever we may think of them nowadays, are extremely helpful to genealogists. If used accurately at the time, these three terms describe:

- Mulatto: Someone with one Black parent

- Quadroon: Someone with one Black grandparent

- Octoroon: Someone with one Black great grandparent

Today in Britain, we would usually say 'mixed race' instead.

What is interesting, and curious, is that all of these terms are read in terms of Blackness – an 'octoroon' person, for example, would have had seven white great-grandparents and one Black great-grandparent, yet it is that eighth great-grandparent who is regarded as being the marker of identity. That in itself is a reflection of society and its attitudes at the time.

At Findmypast, we're committed to making family history more accessible to people of all backgrounds. Through this series of articles celebrating Black British firsts, we hope to highlight the achievements you may not have read about in your school history books. After all, Black history is part of British history.

Black British History FAQs

Who were the first Black Britons?

Black people have been in Britain since as early as the 2nd century AD. Long before the advent of British imperialism, these men were among the ranks of the Roman armies that were stationed along Hadrian's Wall under the leadership of Black Roman Emperor Septimus Severus.

When did slavery start in England?

Britain played a key role in the transatlantic slave trade from 1562. Controlling the triangular route between Europe, Africa and the Americas, Britain was the biggest slave-trading country on the globe by the mid-18th century.

Why is it hard to trace African American ancestry?

There are few accurate family history records earlier than the 1870 Census available to African Americans looking to trace their ancestors. While records may be available in some instances, enslaved people's records were often handwritten and poorly organised, making tracking them down in the 21st century (and building a far-reaching African American family tree) incredibly tough.

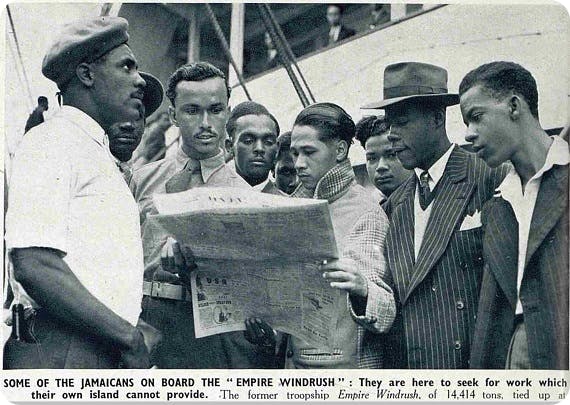

How do I find my Jamaican ancestry?

Findmypast's CaribbeanAncestry Hub contains a wealth of records that may just be able to help you. You can use birth, marriage and death records to establish key details about your family members, and from there, begin a flourishing family tree. Explore Findmypast's Jamaican records and Jamaican newspapers today.

Related articles recommended for you

10 tips for searching the 1939 Register like a pro

Family Records

Explore new Jamaican records and two national newspaper titles

What's New?

Who Do You Think You Are? Series 21: here's what you missed

Discoveries